Alaska's rape rate is the highest in the country --

three times the national average. To find out why, I went to Alaska to

talk with victims, politicians -- and the rapists. You voted for me to

cover this topic as part of CNN's Change the List project.

By John D. Sutter

Videos and photography by Brandon Ancil

Videos and photography by Brandon Ancil

========

Alaska (CNN)

Stand

outside Ruth's wooden home here in Alaska and you'll hear only an

occasional sound: A plane buzzes overhead, a reminder that the only way

in or out of this village at this time of year is by air. Snowmobile

tracks in her driveway, fossilized by the cold, creak and pop under your

feet like brittle Styrofoam.

And the wind: The constant shhhhh as it rattles the tundra.

It sounds almost like a whisper.

Like this land is keeping secrets.

Next to Ruth's house is a shack: One room,

wood stove, metal roof. Its plywood walls are so leaky that socks and

towels are stuffed in the holes. In the shack lives Ruth's husband,

Sheldon – love of her life, father to her many adopted children, a few

of whom live with her next door. A clothesline, maybe 30 feet long,

connects the homes. Ruth met Sheldon decades ago while ice fishing – was

introduced by friends. He shared her love for the outdoors, her passion

for camping all summer, soaking in 24 hours of sunlight afforded by the

severe tilt of the Earth up here.

She loved him then. And she loves him now,

she told me as we sat in her living room, wind chimes clanging outside

on the porch. At least she thinks she does.

It's been harder lately -- since she learned what Sheldon was hiding.

Ruth told me her world nearly collapsed that

day in 2003 when the police said her husband, over a course of years,

had been raping and molesting Alice, one of her adopted daughters. Those

unthinkable acts happened in her house, without her knowledge, she

said.

But, amazingly, Ruth and Alice have opened their hearts again to Sheldon.

The mother and daughter have consented to

ongoing contact with him, allowing him to live next door, for a powerful

and counterintuitive reason:

They never want him to rape again.

'We can't answer that...'

I spent more than two weeks in America's

"Last Frontier" state in December trying to answer two questions: Why is

Alaska the national epicenter for rape?

And, more importantly, what can be done to change that?

Readers prompted this quest when they voted

for me to cover rape and violence against women in the United States as

part of CNN's Change the List project, which seeks to bring attention

and support to bottom-of-the-list places like Alaska. This is the second

of five topics readers commissioned as part of the series.

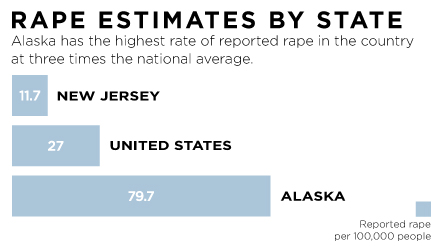

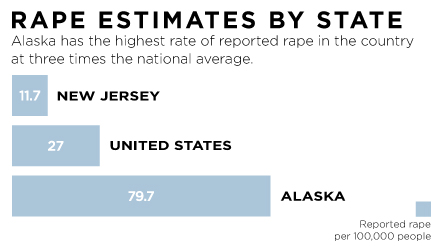

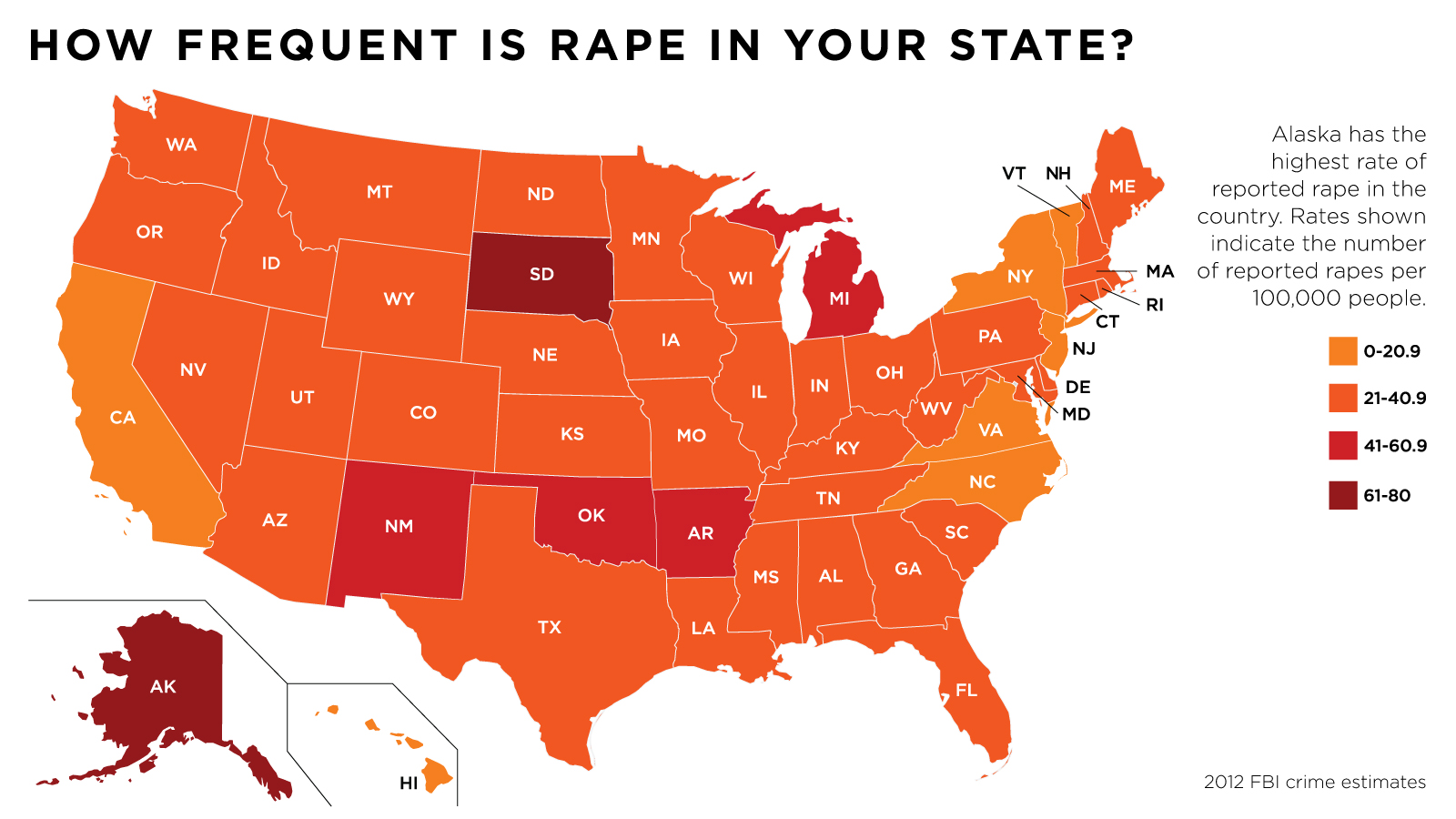

The extent of Alaska's problem with violence

against women is both horrifying and clear: Alaska's per capita rate of

reported rape is the highest in the country, according to 2012 FBI crime

data. An estimated 80 rapes are reported in Alaska for every 100,000

people. That's nearly three times the national average of 27; and almost

seven times the rate in New Jersey, the state where reported rape is

least common. Those comparisons are imperfect, of course. But localized

surveys in Alaska paint an even bleaker picture. A majority of women –

59% -- have experienced sexual or intimate partner violence, which

includes physical violence and threats; and 37%, nearly four in 10, have

been raped or sexually assaulted, according to a survey of 871 adult

women in Alaska, published in 2010.

Source: FBI Uniform Crime Report, 2012

Source: Alaska Victimization Survey

Source: Alaska Victimization Survey

There was a time when politicians in Alaska

argued rape survivors were simply reporting rape more often in this

state than elsewhere. Those arguments, however, have been largely

abandoned as the scope of the violence has become clearer. If anything,

the taboos surrounding rape here would suggest that the crime is

underreported in Alaska, relative to other states.

What's unclear is exactly why the violence is

occurring. "That's part of the problem," said Andre Rosay, director of

the University of Alaska Anchorage Justice Center, and a national expert

on this issue. "We can't answer that question. ..."

I asked Rosay what researchers had done to

try to make sense of it. Had there been efforts to interview rapists? To

understand what life experiences may have led them to rape? Or to try

to figure out what might stop perpetrators from raping again?

No, he said. Not to his knowledge.

But, he offered: Maybe that would help.

That conversation and others like it led me

to the small community where I met Sheldon – and to the decision to

focus on offenders rather than victims. A common refrain from women's

rights activists is that "rape won't stop until men stop raping."

I couldn't agree more. Victims aren't to blame; rapists are.

That's why I'm sharing the story of a rapist -- and a state -- trying to reform.

'There's no hiding'

I met Sheldon, the man who raped and molested

his stepdaughter, in a cluttered conference room in the back of a metal

building in rural Alaska. To protect the identity of Sheldon's victim,

I've changed her name as well as those of her family members, including

her rapist. I'm also not revealing the name or characteristics of their

community.

On the wall in the conference room was a

poster of the logo for an innovative sex-offender treatment program that

Sheldon is enrolled in: The image shows six people holding hands in a

circle around a masked face.

Above the logo is this phrase, translated from the local language:

"Sexual abuse ends when we begin to talk."

The program surrounds rapists and child

molesters who already have served jail time with a network of at least

five "safety nets" -- volunteers from the community who try to prevent

the offenders from raping or molesting people again.

Sheldon is the person at the center.

His wife, Ruth, and several others are the safety net.

In this region, there are at least 300 of these volunteers.

The idea is based on two concepts dear to

local indigenous culture: community and forgiveness. In many states,

from California to Alabama, sex offenders essentially are banished from

their homes after they're released from prison. Offenders are not

allowed to live within a certain distance of schools, parks or

child-care facilities – pushing them into places where they fly under

the radar, unsupervised.

They often end up in homeless shelters,

beneath overpasses and in rural environments where it's difficult to

find work, support and counseling.

The goal here is exactly the opposite, said

the clinical director of the local sex-offender treatment program, and

who I'll call Robert.

Offenders are "right in the center" of a support circle, he said.

"There's no hiding here."

Sheldon entered the room, ready to talk,

wearing a plaid shirt and camouflage-pattern pants. He's a friendly

seeming guy with the face of a marionette – all eyebrows and cheekbones.

Big smile, hard to read.

A man in his 60s, Sheldon moved back to this

community in 2008 after being released from prison in another part of

Alaska. His probation officer helped enroll him in the state-funded

program, which was new at the time, Robert said.

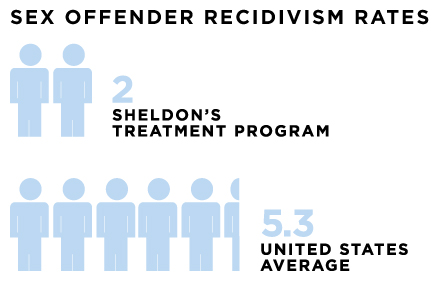

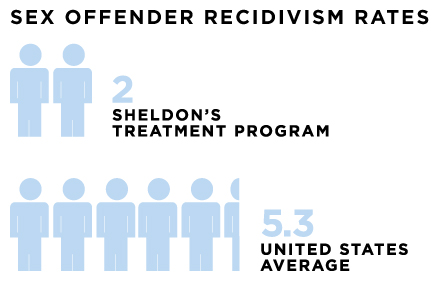

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Alaska treatment program

Since it began, the treatment program here

has served 90 sex offenders, with only two known cases of sexual

re-offense, according to Robert. It's a tiny sample, so it's difficult

to draw broad conclusions, but that's a recidivism rate of about 2%,

which is "pretty darn good," to borrow Robert's words. One study of

9,691 sex offenders nationwide found 5.3% reoffended within three years.

Our first conversation began with Sheldon

telling me he welcomes the fact that the members of his "safety net"--

his wife, a law-enforcement official, a religious mentor, a tribal elder

and others – watch his every move. He also blamed himself alone for the

trauma he caused his stepdaughter, who turned him in.

"I'm taking full responsibility. I'm sick and

tired of holding it in here," he told me, later. "I just need to puke

it out. Vomit it out."

Sheldon confessed to authorities in 2003, as well.

"Looking back is so disturbing for me,"he said. "It's frightening."

'Anger? Anger'

As a young boy, Sheldon learned the ways of

traditional indigenous people: speaking the language, which is full of

hard "k's" that pop in your throat and twisting "g's" that are nearly

impossible for outsiders to pronounce; hunting for blubbery seal;

foraging for salmonberries; and hooking fish out of holes cut in the

ice.

No one calls him it today, but Sheldon's

indigenous-language name roughly translates to "a person you can go to

for help." It was passed down, as is customary in the culture, in honor

of an aunt who died shortly before Sheldon was born.

It would be years before the irony of that name would sting.

Demons haunted Sheldon from childhood.

When he was 7 or 8, he told me, an older man

took him into an abandoned building and made Sheldon unzip his pants.

"He fondled my genitals," Sheldon said. "I backed off and ran away. He

tried to coerce me to cooperate with him: Candy, pop. He asked me if I'd

seen my mother naked in the house."

The abuse continued for years.

"At the time I was so confused,"Sheldon said.

"Who am I? What is the expectation of this man? How am I supposed to

respond to him? Confusion? Shame? Anger? Anger. Because he wouldn't

listen to me when I told him to stop."

By the time he was 10, Sheldon decided to tell his parents.

It was an act of desperation, an enormous leap of faith.

Their response ended up haunting him as much as the abuse.

"Dad pulled my ears and hair and called me a

liar," Sheldon told me. He "said I'd never change – would be a no good,

mischievous boy ... I don't ever remember this man being arrested,

reported. Sometimes it scares me. Maybe I was not the only one."

After being blamed by his father for the

abuse, Sheldon made a vow: He would keep the abuse secret, deep inside

his soul – and never let it surface.

"I've got to be a man," he thought. "And carry this with me alone."

'I could hurt them, too'

It's impossible, of course, to determine why a person becomes a rapist.

But I got some clues as I sat in a circle

with about a dozen rapists and child molesters, along with three

mental-health counselors, in the lobby of a local church.

The men, all clients of the sex-offender

treatment program here, shook my hand and welcomed me to town. Are you

used to this weather? How far are you from home? They wore ski bibs,

hoodies and, in one case, a furry coat. I'd never have known these men

were offenders had we met elsewhere.

Isolation in Alaska contributes to the state's high rate of reported rape.

Sheldon was in the circle, holding a

directional microphone hooked into a pair of headphones that look like

they were purchased with a Walkman tape player. He pointed the

microphone at the men in the circle so he could hear.

It's important he takes in every word.

Sheldon aimed the mic at the counselor from the treatment program here.

How many of you were sexually abused as children? the man asked.

It's a question that had been on my mind.

A little fewer than half of the men in the

circle raised their hands. (Nationally, about 30% of sex offenders were

abused as children, according to a 2001 study that's widely cited by

state governments and activists.)

Later, Sheldon pointed the microphone at me,

and the group allowed me to ask a question. I told them that I came to

Alaska to try to understand why rates of rape and violence against women

are so high here. And I said I figured maybe someone in this group

might have answers. Could they help me understand?

One man who was sexually assaulted as a child

told the group that he abused other people "so I could hurt them, too.

So I wouldn't be alone."

Another said he kept his own sexual abuse

hidden for nearly 60 years. "If I opened up back then, when I was

young," he said, "I probably wouldn't be in this situation."

"My personal experience, what started it all," another said, "was feeling unloved."

Sheldon's story, as well, starts with the abuse he suffered as a boy.

The way his counselors describe it, he became

intensely "sexualized" by those incidents (Sheldon says he was abused

by a man and multiple women in his village as a boy) without

understanding what that meant. That doesn't sound uncommon. I spoke with

an Alaska state trooper who said authorities have responded to rape

cases where the perpetrator is a boy of 7 or 8. It would be years before

Sheldon would rape someone, but his patterns of abusive and

inappropriate sexual behavior and touching began very young. Sheldon

dived underwater in swimming holes so he could touch the genitals of his

female classmates without their knowing what happened. He ran up to

girls at school and fondled their breasts.

He was able to get away with it, he told me,

because he lived in a remote village. Dozens of villages in Alaska have

no law enforcement presence. Troopers must fly in by plane. Some victims

of Sheldon's abusive touching tried to turn him in, he said, but they

either weren't believed or no one thought to take action. Authorities

were never involved. Either the acts were unspeakable, or worse: They

were too common.

'What you've done'

Nearly every square inch in Ruth's living

room is put to use: In the center of the floor is a trash can full of

ice Sheldon harvested from a river, and which they use as drinking water

after it melts; the kitchen table is a swap meet of dried salmon

scraps, coffee mugs, a bowl of seal oil and a Crisco jar; triangular

sticks of firewood are stacked in the corner near the wood-burning

stove; seal-skin mittens, which Ruth sews, are on the coffee table; and,

most eye-catchingly, family photos are everywhere -- papering the

walls, even hanging from a rope.

Video: Visit Nunam Iqua, a remote village with no local law enforcement presence.

Above a bay window, which looks out toward

the shack next door, there's a portrait of the entire family taken in

2001, before Sheldon went to prison.

Sheldon sports his characteristic slim

mustache and Ruth wears saucer-sized eyeglasses, her salt-and-pepper

hair parted in the middle, her son Samuel's hands on her shoulder.

Sheldon is standing next to Alice, the young woman he raped -- after

coaxing her with candy and telling her to be quiet, he told me.

Alice is smiling in the photo, and wearing a lime-green sweater.

She was always the pretty one. "We treated

her like a little doll," Ruth told me, her voice beaming. "We were happy

to have a little girl, and she's always dressed up really pretty." She

was strong, too, Ruth said. Strong as any of her boys. And able to fish

with the best of them. "We were so happy to have her," she said.

Behind the young woman's smile, though, were years of trauma.

The abuse "started off maybe when she was 6,"

Sheldon told me. "Touching her genitals outside her clothes. Pressing

our genitals together. She was fighting that -- didn't want that ... All

I heard was 'no,' but I kept at it. I remember I was mostly intoxicated

at the house. She'd be sleeping in her bedroom and I'd sneak over there

and touch her while she's sleeping, being careful not to wake her.

"Then if she stirred, I'd sneak off."

Alice realized what was happening.

"When I was getting

molested, I was really scared to tell anybody," she said. "I tried to

tell my mom, but she was too drunk to understand me. She was passed out.

She was just grunting. If she would have known, she would have called

the police right away."

Ruth, now sober, did not recall that incident.

Alice told me it was the only time she got up

the courage to reach out for help. She was 9 at the time, she said.

That's the age she recalls the sexual abuse beginning.

"I was too scared" to speak up again, she

said. "I was scared everybody would blame me, or everybody would not

believe me. I was scared they would get mad at me."

Ruth told me she blames herself for not

knowing about the abuse. "I should've known," she said. The signs –

depression, doing poorly in school – seem so clear in retrospect. If

only her daughter felt like she could talk. Or if only she had heard.

In the silence, the abuse continued for seven years.

'EFFECTIVE. WORKS.'

Sheldon goes on long walks in the morning

when the sun comes up, which is around 10:30 or 11 a.m. in December. The

light peeks over the horizon and hovers there for a few hours, bringing

no warmth (it was consistently 0 F, day and night, while I was in the

area) but burning through the eyes of anyone who dares to look. The sun

in wintertime Alaska reminded me of that painful part of an eye exam

when the doctor puts the light right up to your pupil, hoping to see

what's invisible.

Sheldon meditates and prays as he walks,

asking God to heal him. Ruth, like the sun on the horizon, never takes

her eyes off Sheldon. She calls and texts any time he's away, even

briefly. Where is he now? Has he been around children?

She's a 24-hour police force.

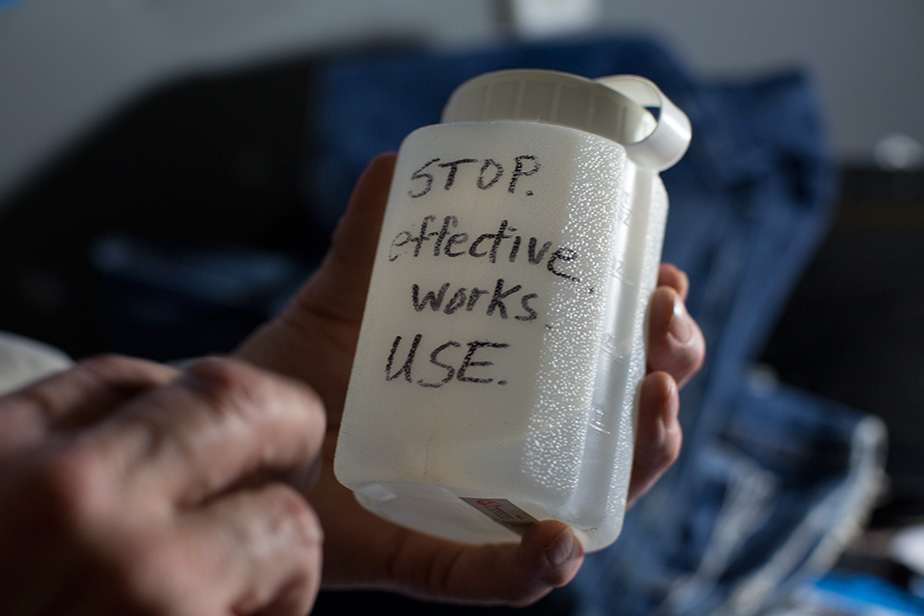

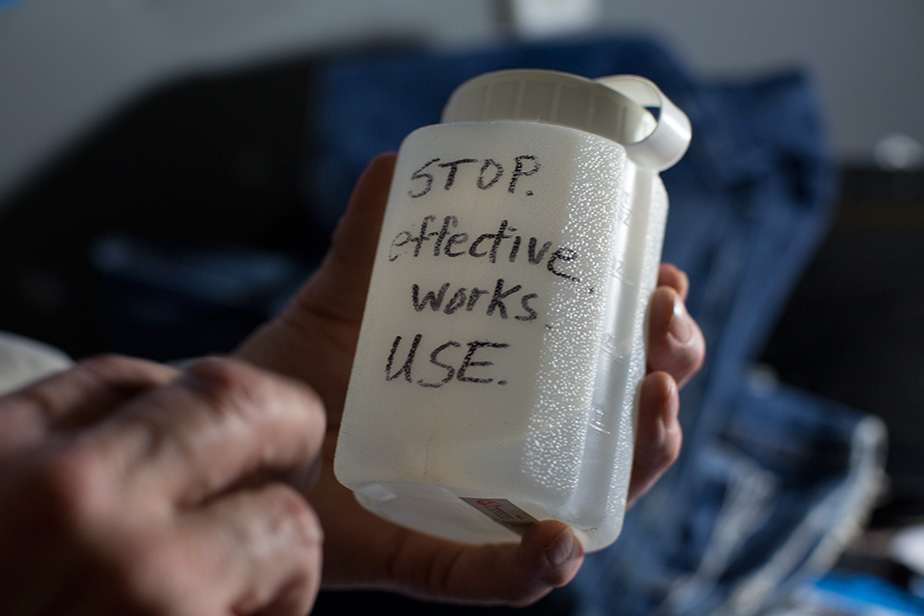

And then there's the ammonia.

Sheldon carries a vial of that chemical with

him everywhere he goes. He keeps a plastic jug of it on a shelf near his

bed in the shack, near a picture of his family that he's stuck to the

wall with electrical tape. These words are written on the side of the

bottle in black, permanent marker: "STOP. EFFECTIVE. WORKS. USE."

Sheldon sniffs ammonia when he gets inappropriate sexual urges.

If Sheldon gets an inappropriate sexual urge, he opens the vial and sniffs.

The chemicals jolt his brain back to reality,

like "boom, your breathing stops," he said. "You can't breathe, your

mind is going haywire."

His counselors prescribed it. For a time, he

had to use it several times a day – every time a woman brushed his arm,

every time he saw young girls.

"At first, I was practically using it all day

– and at night," he said. "I would get up at night. I would get these

very disturbing dreams."

Lately, it's been less frequent.

That's good news.

But every sniff of ammonia is a moment he could offend again.

'R-A-P-E'

Sheldon didn't know the word for "rape" in

English until he'd already perpetrated that crime on his stepdaughter.

When he learned the word and the meaning, he said, after hearing it used

on an indigenous-language radio show, he started to panic.

He asked a priest about it.

"R-A-P-E."

The priest literally had to spell it out, he told me.

Internally, Sheldon wondered: Is that what I've done?

"The darkest moment that I felt was like

this: I know it's wrong but it's something I wanted. I know it's wrong

but I'm so excited. I'm all aroused.

"I can't stop myself."

His stepdaughter was 15 or 16, he said, the first time he raped her.

He raped her quietly, trying "to keep her calm."

"I was careful," he said. "If I raped her forcefully, she is going to yell and scream."

These details were painful for me to hear.

I'm sure they're hard to read. I included them not to open old wounds

for Alice and other victims of sexual assault, but to give you a sense

of exactly how horrifying his crimes are. That so many women in Alaska

have suffered similarly is almost unthinkable.

Think back to the statistics:

-- 37% raped or sexually assaulted

-- 59% victims of intimate partner and/or sexual violence

It's clear Ruth would like to reassemble her

family the way it appeared in that portrait hanging over the bay window.

Everyone together and smiling.

But she knows the truth: Smiles hid the horror, then and now.

Alice talked with me by phone only after I'd

left Alaska. While I was in the community, she was drinking heavily and

staying away, she told me. When we spoke, she sounded sober and of clear

mind. I called her on her mother's phone and she told me she was

staying at home again. Alice has had trouble with substance abuse since

she was a young girl, she told me. Started smoking pot at 12 and

drinking by 14. She did it "to forget what happened," she said, "but it

was always still there."

She was in rehab for alcohol abuse as a

teenager when, in an outburst that surprised even her, Alice told a

counselor she had been molested by Sheldon. She never intended to tell

anyone – not after the experience with her mom.

Life hasn't been easier for her since. She

got married while Sheldon was in prison, but she had trouble being

intimate with her husband because images of her childhood abuse flashed

to mind. "There were some days I would feel uncomfortable having sex,"

she said. "He would ask what was wrong. I didn't tell him."

Several years ago, her only child, an infant

son, died unexpectedly of an illness after suffering from a long and

nagging cold, Alice told me.

"I imagine how tall my son would be. I just imagine he's going to school."

Then, less than two years later, her husband

drowned in a river when their boat sank. She was on the boat, too, and

she threw him a gas container in hopes he could use it to float to

shore. "I heard him say, 'I can't swim anymore,'" she said.

It was around that time that Sheldon was released from prison.

When Alice's mom, Ruth, decided to let

Sheldon back into their lives, she made sure he understood how much pain

he had caused their family. She met Sheldon not at the airstrip but on

their frozen driveway. As Sheldon recalls it, she pointed to the shed

beside her home and told him that this is what he had done – that the

torn-up building was a visual manifestation of the invisible wreckage

inside them all.

Sheldon looked over at the shed: Broken windows, a door off its hinges.

A violent couple had rented it, Ruth told me, and destroyed it.

"I hope you see what you've done to us here," Sheldon recalls Ruth saying.

"And she left me there."

'There's hope'

I couldn't help being alarmed when Sheldon told me about the ammonia.

After spending several days with him, it

became possible, in brief interludes, to stop thinking about the fact

that he had raped his daughter. But certain moments -- like hearing

about the ammonia -- would spring me back to a very frightening reality.

This is a man who counselors say can never be trusted, not 100%; who

does everything he can to seem like he's on the right track; who, his

therapist told me, had sex with a dead and frozen seal once because he

was so aroused.

"I know (Sheldon) is changing," Ruth told me.

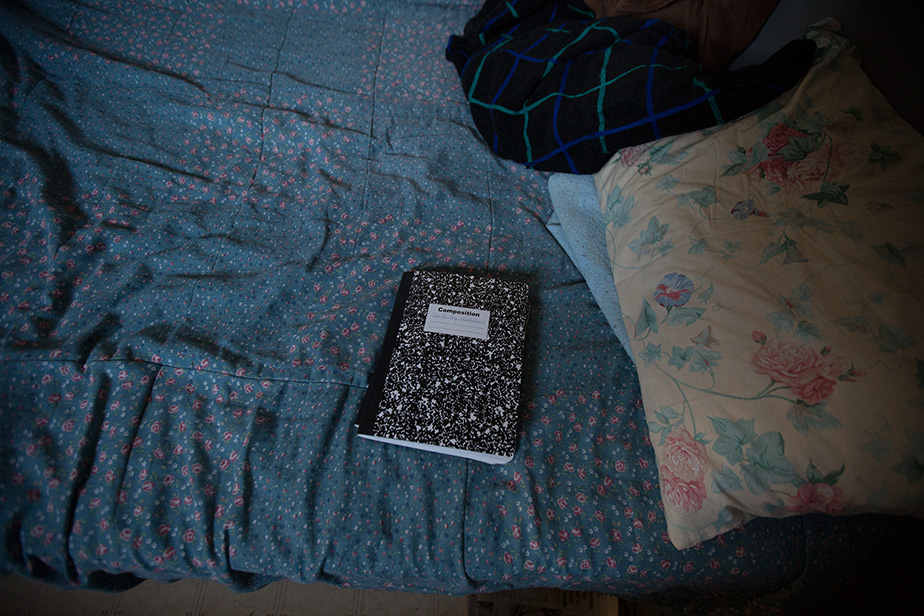

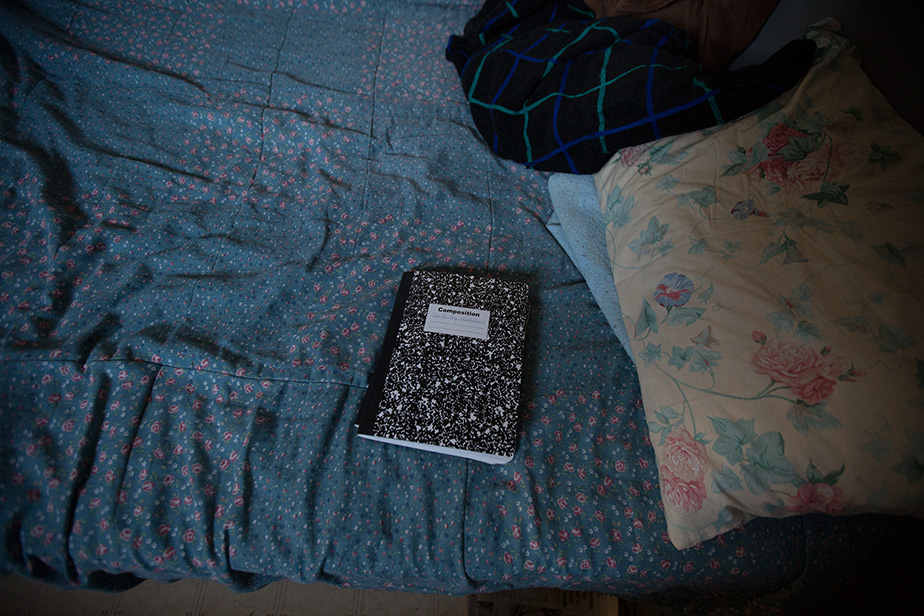

Counselors ask Sheldon to keep a journal about his progress and sexual thoughts.

Still, she worries.

And how could a person blame her?

Sheldon's struggle makes Ruth and Alice's

acceptance of him – and this community's – all the more powerful. I went

to church with Sheldon, accompanied him to the post office, met the

family's priest, saw Sheldon read and watch TV with the couple's young

son. In none of these interactions did people seem to treat him

differently. If anything, he seems to be a caring and loving father to

the young boy.

The intellectual part of me understands this is best for everyone involved.

But it's hard not to retch at what he's done. How can you forget?

Ruth and Alice wrestle with these questions, too.

The terms of Sheldon's probation initially

banned him from having any contact with his daughter, according to court

documents. Alice, now in her mid-20s, has allowed Sheldon to live next

door to her mother and to be in her presence while he is in recovery,

said Robert, the clinical social worker from the program. That wouldn't

have been legal without her consent, he said. Sheldon is not allowed to

be in the presence of minor females without supervision, according to

the terms of his probation.

Ruth is quick to police these points. That's

one reason she wants Sheldon to live next door in the shack, instead of

where he can't be watched.

Alice told me she approved the arrangement.

"I'm completely fine with him being around –

just as long as my mom's around or somebody's around with us," Alice

told me. "I feel safe as long as he's not sleeping under the same roof

... I believe he can change. If he could believe in me to succeed in

school, I believe he could change. I know that changing is possible.

"I can't tell you the future or anything," she said, "but there's hope."

I asked if she had forgiven Sheldon.

To my surprise, she said she has.

"We were taught: forgive and forget," Alice

said, "but I can't forget, and I won't forget ... I can forgive him but I

won't forget ... It's a scar for life."

Her mother wants to forgive him but can't,

not yet. She's considered leaving her husband. I'm sure that's what many

readers would expect – or demand – her to do.

But she thinks about it rationally, practically.

She knows many sex offenders end up homeless.

She knows, too, that, without her, Sheldon would be more likely to reoffend.

She considers this her unwanted calling. Ruth

comes from a highly religious family. She's a stout believer in

forgiveness and redemption -- a person who used to take a large number

of foster kids into her home, because she wanted to help them. She walks

around town and many of these children call her "Mom." She knows –

believes, with all her soul -- Sheldon can change. And Alaska can, too.

It can, right?

Sometimes she has to wonder.

'All of the secrets'

Before I visited Alaska, it was difficult for

me to comprehend how stunningly common rape is in this state. As an

outsider, when I heard about Sheldon's situation – a rapist living next

door – I was flabbergasted.

That kind of situation isn't unheard of here.

It would be possible in any number of communities, activists told me.

There are so many perpetrators, so many

victims. Communities in Alaska are small enough there's little choice

but for lives to intersect again.

That was true enough in a 200-person Yupik

village I visited, out by the mouth of the Yukon River. Nearly every

woman in Nunam Iqua has been the victim of domestic abuse or sexual

assault, according to several women there, a nearby women's shelter

director, and the village's mayor. Nunam Iqua means "end of the land" in

Yupik. It has no local law enforcement. When rape or other violence

occurs, state troopers must fly into the village from other towns – a

process that sometimes takes days, depending on the weather. A local

husband and wife run a secret "safe house" for victims of sexual and

intimate partner violence. To get formal help, however, victims would

have to fly to a nearby town.

Abuse becomes normal in such an environment.

The PBS series "Frontline" visited one

village where Catholic workers were alleged to have sexually abused

nearly an entire generation of Alaska Native children in a rural part of

the state.

There are decades of sordid history that need to be unpacked.

Many people here talk about the

"multigenerational trauma" that has been inflicted on Alaska Native

people, who are thought to have among the highest rates of rape and

other violence. Entire generations were subjected to abuse as well as

disease.

It's still within cultural memory, for

example, that white missionaries and settlers brought flu that wiped out

entire villages of Alaska Native people in 1918. "Suffering from

influenza, many Eskimos and Native Americans found themselves unable to

harvest moose or feed their traps and, in the wake of the pandemic, many

people died of starvation," the U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services says on a page devoted to the flu. "In some areas, the

situation was especially acute as Eskimos did the unthinkable and ate

their sled dogs. In other villages, hungry sled dogs turned on the dead

and dying and ate them to survive."

Decades ago, children were punished harshly,

beaten even, if they spoke their native language. Sheldon witnessed this

as a child. And, like many others, he went away to boarding schools for

indigenous people in Oklahoma and Kansas – foreign lands where he was

disconnected from his roots. "It was totally a culture shock for me," he

said.

Most of these traumas remain unspeakable

today in rural Alaska. It's as if generations of elders have dealt with

the past by silencing it. Experts tell me this is one of the reasons

rape has been allowed to flourish. Generations of people are wandering

the tundra lost – unemployed, drunk, angry, suicidal and violent.

"All of the secrets and the harm – the sexual

violence – came after contact" between Alaska Natives and white

settlers, said Joan Dewey, mental health clinician who works with sex

offenders and has been trying to understand rape in the state.

None of this is an excuse for violence. There

is none. But it does go a long way toward explaining why Alaska has the

highest rape rate in America.

It would be a mistake to see rape as an isolated problem.

It and so many other social ills grow from the same root.

The social fabric of Alaska has been torn.

'I didn't feel human at all'

Of all the unique aspects of Sheldon's

treatment program – the ammonia, the therapy sessions, the idea that sex

offenders should be kept close, not pushed away – the most powerful to

me is this: victims are among the volunteers.

I met a woman -- I'll call her Claire -- who

was sexually abused by her brother as a young girl in a remote village,

and who was raped by a taxi driver as an adult in Anchorage. After all

of that, her daughter, a product of that rape, was sexually abused by

her nephew after Claire gave the girl up for adoption.

I'm not using Claire's real name or image in

an effort to further protect the identity of Sheldon's victim. She was

willing to speak openly, with her image and name. The soft-spoken

42-year-old with porcelain features and a beaming smile is convinced

that, in order for Alaska to stop sexual violence, victims of rape need

to speak up.

And perpetrators need to be given the opportunity to change.

Those beliefs come not in spite of but because of her personal experience.

Claire's brother started abusing her when she

was 9 – coming into her room late at night and pressing his genitals up

against her, with their sister in the room.

"The next day I tried to tell my mom," she

said. "I don't know if they were in denial, or if they didn't want to

face it. I don't know ... I just stopped telling my parents" after they

didn't do anything to stop her brother from abusing her.

"It was like, do I exist?" she said. "Do I even have a voice?

"Can't anyone hear me crying?"

It seems no one cared to hear. Claire was

left to try to protect herself. She climbed in bed with her sister, who

promptly pushed her out. She wore layers of cold-weather clothing --

piled blankets on top of that, hoping to deter him, or slow him down at

the very least. She still hates the month of October because that's when

the abuse always escalated, as Alaska's nights grew longer, stealing

the day.

At 16, Claire told a teacher – turned him in.

But the community blamed her, and her family disowned the high-school

girl. She has to wonder, now, if it's because she was female and he was

male. She didn't work and he hunted and fished – provided not just for

her family but also for the entire Alaska Native village.

He was seen as valuable; she was not.

She ended up in foster care, part of the time in Anchorage, the city where she later would be raped.

People in this state have done everything they could to break Claire's spirit.

But it hasn't worked.

Two years after the rape in Anchorage, which

she said she did not report because she was afraid she would be blamed,

just as she was at home, Claire had a son from a consensual

relationship. She decided to seek help – to find a group of women in her

community who she could talk to about all of the shame and grief she

carried.

"The perpetrator makes you feel so ashamed –

like it's all my fault," she said. "It's what I wore. I don't deserve to

feel love. I don't deserve to feel happy. There's a lot of things that

my mind said ... I felt so dirty, so unclean.

"I felt worthless. I didn't feel human at all.

"I felt like I was just a thing."

Talking about it helped Claire realize that she was not to blame.

The shame was theirs, not hers.

She decided she wanted a different life for

her infant son – didn't want him to be "born under the shadow of my

ancestors' trauma," she said, as she was.

Now she is working with Sheldon's

sex-offender treatment program. She's a "safety net" member, helping the

nephew who sexually abused her own daughter. She believes he – and

other sex offenders in Alaska – can change.

It's with Mandela-esque compassion that she

says the state is failing them -- that communities must be rebuilt so

they're safe for everyone.

So they don't encourage violence.

She thinks back to something an elder told her ages ago.

"He used to say, 'Our people are sleeping,'"

she told me. "'They're in a daze. They don't know what they're doing.

So, the people who are ready, they need to prepare them a big feast.

Prepare them their meals, because they're starting to wake up.'"

I asked Claire if she had any advice for Alice, Sheldon's victim.

Her answer was quick: Talk about it.

"You need to stop carrying the shame," she

said, knowing that's easier said than done. "We need to stop wearing the

masks that (the rapists) put on us."

'I told him to stop'

Sheldon's family has been settling into a new

normal of sorts. Each day is difficult. Sheldon and Ruth don't talk

like they used to. He spends his days doing chores – chopping wood,

repairing her house – while she works temp jobs. Alice is living at home

for now, but she's been in and out in recent weeks.

They live partly off Sheldon's pension from

the Alaska Army Reserves, where he served for more than two decades.

Their son, Samuel, chips in financially, too.

But Ruth owns both of their homes, their car

and their snowmobile. Her income, from office jobs as well as selling

indigenous art and clothing, makes it work. Some women feel trapped and

stay with abusive husbands because they are financially dependent; it

would be impossible to say that of Ruth.

One victim of rape and sexual

abuse said she fears Alaska's long, dark winters because that's when the

abuse became more frequent.

Sheldon tries to give back however he can.

It's clear to me he wants to redeem himself, and is pained to see his

stepdaughter struggling. He volunteers with search-and-rescue teams –

helps translate the local language for sex-offender counselors. Walk

around town with him and people smile and greet him like any other

person.

It's almost surreal how much has changed.

"He hasn't re-offended, to our knowledge," said Sheldon's counselor, "and I think the polygraph would show us if he had."

But the work is never ending.

Sheldon's counselor has reservations about

him living so close to his daughter. He wants him to be integrated into

the family and community – it's safer that way.

But it's hard to know how close is too close.

Whether it's possible to

reform rapists and sex offenders is perhaps the most controversial topic

in advocacy and policy circles at the moment, said Scott Berkowitz,

founder and president of the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network

(RAINN), a leading advocacy group. Still, he shares my view that "we've

got to keep trying," he told me, "even if it only is working 10% of the

time."

It's easy to see why when you spend time with Sheldon and his family.

Alice has been quicker to forgive Sheldon

than Ruth because Sheldon admitted what he had done -- and that was a

life-changing thing for her, she told me. When her abuser came back from

jail, he told her that she was not to blame.

"It just made another block come off my shoulders," Alice said.

Samuel, one of Sheldon and Ruth's sons, had a

similar experience. I met the 20-something in his room in the back of

Ruth's house one afternoon. A curtain covers his door and I had to climb

over clutter to reach the room. I had planned to ask Samuel about his

dad's recovery, how his sister was doing, and how he felt about having a

father who raped a family member. Was it safe? Did he know about the

abuse? It is safe, he said, and no, he's not afraid of Sheldon.

Samuel told me he also was a victim of rape, too, by a stranger, not by Sheldon

"I told him to stop and get off" of me, Samuel told me. "He wouldn't."

The rape happened behind an abandoned

building when he was 15, Samuel told me. Samuel, who is gay, has

flashbacks to the rape whenever he gets close to someone now –

especially if they're about to become intimate. He worries he will be

raped again. That fear, and the flashbacks, have led to depression,

shame and failed relationships and some trouble with substance abuse and

the law.

The one bright spot in it all, he said, is what his dad told him.

"'It's not your fault, (Samuel),'" he recalls Sheldon saying. "'It's not your fault.'"

He raped you. Only he is to blame.

If anyone can say that, it would be a rapist.

'Resident evil'

After talking with dozens of people in

Alaska, here are the best theories I heard about why the state has the

highest rape rate in the country:

- The history of cultural trauma, abuse, disease and dislocation imposed on Alaska Native villages has led to a cycle of despair and violent behavior.

- Rape is tolerated in some communities; when victims like Claire come forward, they're not believed or told to forget what happened.

- Offenders are too rarely punished. Of nearly 1,000 cases of sexual assault studied by the University of Alaska Anchorage Justice Center, 46% were referred for prosecution and 22% resulted in a conviction. It's difficult to compare those rates with other states, said Andre Rosay, from the justice center. What's clear, he said, is that "the biggest hurdle really is in getting the case referred for prosecution, "especially in villages with no local law enforcement presence. Sexual assault cases are 3 ½ times as likely to be prosecuted in communities with a Village Public Safety Officer, he said.

- The state is so large – four times the size of California – and so sparsely populated, that it's nearly impossible to police. State troopers must fly to many remote villages, and that can take days, depending on the weather.

- Long winters make it easy for offenders to perpetrate the crime.

- There's a high rate of alcohol abuse, which doesn't cause rape, but can lower inhibitions for would-be offenders and can be used as a date-rape drug.

If I placed a bet, it would be on a seventh reason: the silence.

It permeates every aspect of life in Alaska.

And it changes how the state must deal with rape and sex abuse.

Policy shifts are important, to be sure. The

state should broaden the power of tribal courts; expand law-enforcement

in rural Alaska; increase the number of women's shelters, so fewer

victims will have to hop a plane to find safety; and expand sex-offender

treatment programs like the one in which Sheldon participates.

But, for those to take hold, people have to start talking.

Some are pushing the conversation, and have been for years.

As I traveled the state, I met Elsie Nanugaq

Tommy -- 104 and all smiles inside a fur-trimmed, hooded coat -- who

started a secret safe house for abused women in Newtok, Alaska, decades

ago. Her extraordinary work – and her willingness to address issues

others wanted to ignore – inspired her granddaughter, Denise Tommy, who

is now the director of the Tundra Women's Coalition. That organization

runs rape-prevention programs and a shelter for abused women. It pays to

fly victims to the shelter from neighboring villages.

In Juneau, I met Alaska's governor, Sean

Parnell. He has none of Sarah Palin's name recognition (the local press

calls him the Oatmeal Governor because they think he's bland), but he's

making important strides in terms of raising awareness about sexual

violence. In an interview, he called rape a state "epidemic," and

Alaska's "resident evil." "That's been the hardest part about the evil

among us: We haven't been willing to talk about it," the governor told

me.

"I'm also sending a message as a man to women

who have endured this shame that they are not to blame," he said. "They

do not need to carry the guilt and shame – and we are willing to

embrace and love them unconditionally."

If you want to help, I'd encourage you to

donate to CNN-vetted organizations that are working to end violence

against women in Alaska.

Or join our online storytelling project: "We

are the 59%." We're asking people to show their solidarity for the

survivors, or to share their own stories of survival.

'Treatment is never over'

Journalists like to classify things – success

or failure; good or bad. So it should be no surprise that I asked

Sheldon's counselor if he considered him a "success story."

No sex offender is a success story, Robert

told me. The harm caused to a victim of rape or sexual abuse can never

be repaired. And there's always the chance of re-offense. "Treatment is

never over for them," the clinical social worker said. "We equate it

with diabetes – a physical disability. It's something you're going to

have to manage the rest of your life." But Sheldon's, he said, is an

encouraging case.

And he wouldn't be in this line of work if he didn't believe people could change.

It's impossible to trust Sheldon – not 100%.

But I am rooting for him. I know he has the potential to grow into the

meaning of his indigenous name: "a person you can go to for help." He

proved that when he encouraged Alice, his stepdaughter and victim, to

pursue her GED diploma. She passed the test in December, she told me.

She said she wouldn't have been able to do it without him.

"He believed I could do it," Alice said.

I also hope Sheldon, Alice, Ruth and Samuel's

willingness to speak about rape in Alaska will help a state -- and a

country -- wake up to the horrors of violence against women, which is

far too often tolerated or excused. Victims must feel comfortable to

talk about the violence they've survived; and family members and friends

have to be ready to listen. It is senseless that so many young people

in Alaska are abused and feel like they must remain silent about it.

That's not their fault, it's ours. If victims believed no one would

judge them or think less of them for coming forward -- if they knew they

would be supported and loved and helped -- this crisis would end.

If reading this story has been at all

unsettling, let that be the most disturbing part: All of us have a role

to play in perpetuating or ending the violence. It already exists in

such high numbers in Alaska that the only way to stop the cycle is to

speak its name -- to stop allowing rape and sexual abuse to be hidden.

Offenders like Sheldon do have a role in that process.

They're the ones responsible for this epidemic.

They can also help stop it.

And they deserve a chance at redemption.

Since I got home from Alaska, I've been

thinking every day about the rapist I met and his family next door. The

details of their stories -- the ammonia, the frozen seal, the flashbacks

they have during sex -- have given me nightmares. I'm disgusted by what

Alice and Samuel experienced. But the more lasting feeling I have is

one of awe -- at the bravery and selflessness they've displayed in

sharing their stories.

It's that kind of courage that will ensure the cycle of violence stops with them.

Alaska could use a few more people like that.

Please join John D.

Sutter and experts from Alaska for a live discussion of this story in

the comments below at 2 p.m. ET / 10 a.m. in Alaska. You can also

message Sutter with questions at CTL@CNN.com or on Twitter: @jdsutter.

The comments will remain closed until that live chat begins. The

opinions expressed in this story are solely those of John D. Sutter.

=======

CNN

Comments